(Second Part of the Series)

As evening falls on Mindoro island, residents rush through familiar rituals — hurried dinner preparations, last-minute homework, quick tallying of shop receipts. Then, like clockwork, the lights flicker and die, plunging communities into darkness.

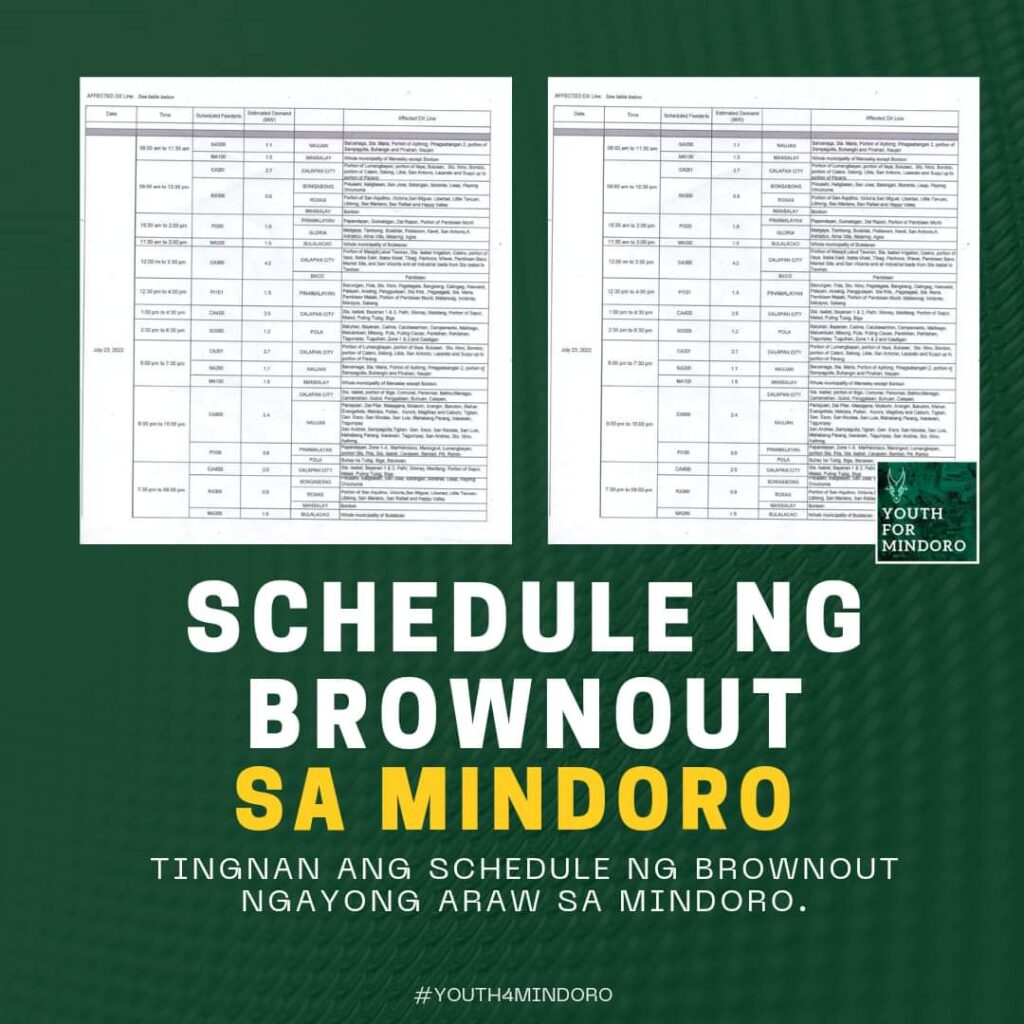

For the 1.3 million people living on this Philippine island, prolonged daily blackouts are an inescapable reality. The current power crisis gripping Mindoro is just the latest chapter in a 50-year saga of energy insecurity.

“We’ve been prisoners of darkness as long as I can remember,” said a retired schoolteacher in Calapan City in a magazine article. “When I was young, we had hope electricity would come soon. Now my grandchildren face the same struggle.”

How did an island rich in natural resources end up mired in an intractable energy crisis?

The roots of Mindoro’s power woes stretch back decades, intertwining issues of geography, governance, infrastructure and shifting national priorities.

ISLAND ISOLATION

Mindoro’s energy challenges stem from its nature as an island. Located off Luzon’s southwestern coast, Mindoro has long existed separately from the Philippines’ main power grids. This isolation preserved much of the island’s natural beauty but hampered infrastructure development and energy security.

In the 1960s and ’70s, as the Philippine government pushed for rapid electrification, Mindoro lagged behind. Connecting the island to Luzon’s power grid via undersea cables was deemed too costly and technically challenging. Instead, Mindoro was left to develop localized power systems.

“From the start, we were playing catch-up,” said an energy policy expert at the University of the Philippines. “While other regions benefited from economies of scale and grid interconnection, Mindoro had to bootstrap its own power infrastructure with limited resources.”

This isolation meant early electrification efforts on Mindoro were piecemeal and underfunded. By 1975, only about 25% of Mindoro households had electricity, compared to the national average of over 40%. Those with power often experienced unreliable service and frequent outages.

DIESEL DEPENDENCE

Faced with the need for rapid electrification but lacking means for large-scale power plants, Mindoro turned to diesel generators as a quick fix in the 1980s. Small diesel power plants sprouted across the island, providing electricity to growing communities.

“At the time, diesel seemed like a godsend,” said former Occidental Mindoro governor Jose Tapales Villarosa. “It was relatively cheap, the generators were easy to install, and we could finally bring power to remote areas.”

But reliance on diesel proved a double-edged sword. While enabling wider electrification, it locked Mindoro into a cycle of fuel dependence persisting today. As global oil prices fluctuated over decades, so did the cost and reliability of Mindoro’s power supply.

The island’s main power provider, Occidental Mindoro Consolidated Power Corporation (OMCPC), still operates primarily on diesel fuel. This leaves residents vulnerable to price shocks and supply disruptions. In April 2023, when delayed subsidy payments prevented OMCPC from purchasing sufficient fuel, large parts of the island experienced blackouts lasting up to 20 hours daily.

“We’re hostages to diesel,” said former Calapan City Mayor Arnan Panaligan, now Oriental Mindoro 1st District Representative, in a media interview. “Our economy, our daily lives – everything depends on those fuel shipments arriving on time. It’s an untenable situation.”

REGULATORY CHALLENGES

Compounding Mindoro’s geographical and infrastructural challenges has been a history of regulatory missteps and mismanagement in the energy sector. The creation of electric cooperatives in the 1970s and ’80s was meant to empower local communities in managing power needs. However, many cooperatives have been plagued by inefficiency, corruption and political interference.

The Occidental Mindoro Electric Cooperative (OMECO), responsible for power distribution in much of the island, has faced particular scrutiny. Allegations of mismanagement and failure to upgrade aging infrastructure have dogged the cooperative for years. In 2022, the National Electrification Administration (NEA) had to intervene to address OMECO’s mounting debts and operational issues.

“The cooperative system was well-intentioned, but it hasn’t always worked as planned,” said one energy consultant at DOE Manila in a World Bank report. “Without proper oversight and professionalization, some cooperatives became vehicles for patronage politics rather than efficient utilities.”

Regulatory challenges extend beyond the local level. The complex web of national agencies involved in the power sector – including the Department of Energy, National Power Corporation and Energy Regulatory Commission – has often resulted in bureaucratic gridlock and delayed decision-making.

This regulatory morass has hampered efforts to attract private investment in Mindoro’s power sector. Potential investors face a labyrinth of permits, approvals and shifting policies that make long-term planning difficult.

“It’s not just about building power plants,” said a former executive at a Luzon-based power plant firm. “You need a stable regulatory environment to justify major capital investments. That stability has been lacking in Mindoro for decades.”

MISSED RENEWABLE OPPORTUNITIES

Mindoro’s struggles with conventional power sources are particularly frustrating given the island’s abundant potential for renewable energy. With mountainous terrain, swift-flowing rivers and ample sunlight, Mindoro is well-suited for hydroelectric, solar and even geothermal power development.

As far back as the 1990s, studies highlighted Mindoro’s renewable energy potential. A 1992 National Power Corporation report identified several promising sites for mini-hydro projects across the island. Yet three decades later, only a handful of these projects have materialized.

Similarly, plans for large-scale solar farms have repeatedly stalled due to funding issues, land disputes and regulatory hurdles. A much-touted 50-megawatt solar project in San Jose, Occidental Mindoro, first proposed in 2016, remains unfinished as of 2024.

“It’s heartbreaking to see all this untapped potential,” one environmental activist said in a UP report. “We could be a showcase for clean, sustainable energy in the Philippines. Instead, we’re still burning diesel while our rivers and sunlight go to waste.”

The slow progress on renewables stems from a combination of factors. Limited local technical expertise, high upfront costs and lack of consistent government support have all played a role. Additionally, entrenched interests in the existing diesel-based power structure have at times resisted the shift to alternative energy sources.

“There’s a certain inertia in the system,” the environmental activist. “Changing course requires political will, significant investment and a long-term vision. Those elements haven’t always aligned in Mindoro’s case.”

NATIONAL PRIORITIES AND NEGLECT

Mindoro’s energy woes cannot be viewed in isolation from broader trends in Philippine development. As successive national governments focused on industrialization and urban growth, rural electrification often took a back seat.

The 1990s and early 2000s saw a push toward privatization and deregulation in the Philippine power sector. While this led to improvements in some areas, it also resulted in reduced government investment in power infrastructure for more remote provinces like Mindoro.

“There was an assumption that the private sector would step in to fill the gaps,” explained former DOE secretary Carlos Jericho Petilla. “But in areas with lower demand and higher costs, that private investment didn’t always materialize as hoped.”

Mindoro, with its relatively small population and underdeveloped industrial base, often found itself low on the priority list for major energy projects. National grid expansion plans repeatedly bypassed the island in favor of more populous or economically vital regions.

This neglect extended to disaster preparedness and resilience. Mindoro’s power infrastructure has been repeatedly damaged by typhoons and other natural disasters over the years. Yet investments in fortifying the system and improving recovery capabilities have been limited.

“We’re always in reactive mode,” said a San Jose LGU official. “After every major storm, we patch things up as best we can, but we never seem to get ahead of the problem.”

HUMAN COST OF ENERGY INSECURITY

Behind the technical and policy failures lies a story of human struggle. For generations, Mindoro’s residents have borne the brunt of unreliable power supplies, with far-reaching consequences for education, healthcare and economic development.

In hospitals across the island, doctors and nurses have become adept at working around sudden power outages. A doctor, who runs a small clinic in Mamburao, keeps a stock of battery-powered lamps on hand. “We’ve had to deliver babies by flashlight more times than I can count,” she said. “It’s not just inconvenient – it’s dangerous.”

Schools face similar challenges. Teacher Carlos Ilagan in San Jose, Occidental Mindoro recalls years of interrupted lessons and canceled classes due to blackouts. This was more palpable during the 2-year Covid pandemic period. “How can our students compete in the digital age when they can’t even count on having lights and computers?” he asked.

The economic impact has been equally severe. Small businesses struggle to operate consistently, while the unreliable power supply has deterred larger industries from setting up shop on the island. This has contributed to high unemployment rates and pushed many young Mindoreños to seek opportunities elsewhere.

“Our brightest young people leave because there are no jobs here,” lamented Ilagan. “And without a stable power supply, it’s hard to create those jobs. It’s a vicious cycle.”

RECENT DEVELOPMENTS

The acute power crisis of 2023, which saw some areas of Mindoro receiving as little as four hours of electricity per day, has galvanized action at both local and national levels. The provincial government declared a state of calamity, allowing for the release of emergency funds to address the immediate crisis.

At the national level, there have been renewed calls for government intervention.

Senator Bong Go has pushed for a Senate inquiry into Mindoro’s recurring power problems, while the Department of Energy has explored the possibility of deploying small modular nuclear reactors as a long-term solution.

Some promising developments in the renewable energy sector offer a glimmer of hope. A 50-megawatt wind farm project in Puerto Galera, stalled for years, has recently secured funding and is slated to begin construction in late 2024. Additionally, several small-scale solar initiatives, including community-based projects supported by the Catholic Church, have begun to take root across the island.

“We’re finally seeing some momentum,” said Ilagan. “But we need to ensure these projects don’t get bogged down in the same old bureaucratic quagmire.”

MULTI-FACETED SOLUTIONS NEEDED

Experts stress that solving Mindoro’s energy crisis will require a multi-faceted approach. Immediate measures like ensuring timely subsidy payments and upgrading existing infrastructure must be paired with long-term investments in renewable energy and grid modernization.

Crucially, there’s a growing recognition that Mindoro’s unique geographical and economic situation demands tailored solutions. “We can’t simply copy-paste energy policies from the mainland,” the DOE argued. “Mindoro needs a comprehensive, island-specific energy development plan that addresses its particular challenges and leverages its natural advantages.”

Such a plan would likely involve a mix of centralized and distributed power generation, combining larger renewable projects with community-based micro-grids. Improved energy storage solutions and smart grid technologies could help manage the intermittency issues associated with some renewable sources.

There’s also a push for greater local control and capacity building. “We need to empower Mindoreños to take charge of their energy future,” DOE said. “That means investing in technical education, supporting local energy entrepreneurs, and reforming governance structures to be more responsive to community needs.”

CAUTIONARY TALE AND CALL TO ACTION

Mindoro’s half-century struggle for reliable power serves as both a cautionary tale and a call to action for policymakers across the Philippines and beyond. It highlights the perils of short-term thinking, the importance of tailored approaches to rural electrification, and the need for sustained investment in energy infrastructure.

As climate change concerns grow and the global energy landscape shifts, Mindoro’s experience also underscores the urgency of transitioning to more sustainable and resilient power systems. The island’s abundance of renewable resources positions it as a potential model for clean energy development in island communities – if the right policies and investments are put in place.

For the people of Mindoro, the stakes couldn’t be higher. “We’ve lost too many years to darkness,” said Elena Santos. “It’s time for Mindoro to finally step into the light.”

TIMELINE OF MINDORO’S POWER CRISIS

1960s-1970s: Philippine government pushes for nationwide electrification, but Mindoro lags behind due to isolation from main grids.

1975: Only 25% of Mindoro households have electricity access, compared to 40% national average.

1980s: Mindoro turns to diesel generators as a quick fix for power needs, beginning a cycle of fuel dependence.

1992: National Power Corporation study identifies potential sites for mini-hydro projects on Mindoro, but few materialize.

1990s-2000s: National push for power sector privatization leads to reduced government investment in remote areas like Mindoro.

2016: 50-megawatt solar project proposed in San Jose, Occidental Mindoro, but remains unfinished as of 2024.

2022: National Electrification Administration intervenes to address mounting debts and operational issues at Occidental Mindoro Electric Cooperative (OMECO).

April 2023: Severe power crisis hits Mindoro, with some areas receiving only 4 hours of electricity daily due to fuel shortages.

Late 2024: Construction slated to begin on 50-megawatt wind farm in Puerto Galera after years of delays.

Early 2024: The National Grid Corporation of the Philippines (NGCP) announced it will construct the Batangas-Mindoro Interconnection Project in which power submarine cable will connect Mindoro to the main Luzon grid come 2027 or 2028. (see first part of the article)

KEY PLAYERS IN MINDORO’S ENERGY SECTOR

Occidental Mindoro Consolidated Power Corporation (OMCPC): Main power provider for much of the island, operates primarily on diesel fuel.

Occidental Mindoro Electric Cooperative (OMECO) and Oriental Mindoro Electric Cooperative (ORMECO): Responsible for power distribution in much of the island, has faced allegations of mismanagement.

National Power Corporation (NAPOCOR): State-owned corporation responsible for power generation and transmission, provides subsidies to OMCPC.

National Transmission Corporation (TRANSCO): Government-owned corporation created to assume ownership, operations and maintenance of the country’s power grid from 2001-2008 until NGCP became operative thru RA 9511.

Department of Energy (DOE): Government agency overseeing national energy policy and regulation.

Energy Regulatory Commission (ERC): Independent regulatory body for the energy sector.

National Electrification Administration (NEA): Government agency overseeing rural electrification efforts and electric cooperatives.

CHALLENGES AND POTENTIAL SOLUTIONS

Challenge: Isolation from main power grids

Potential Solution: Investment in undersea power cables or development of self-sufficient renewable energy systems

Challenge: Dependence on diesel fuel

Potential Solution: Rapid transition to renewable energy sources like solar, wind, and hydroelectric power

Challenge: Regulatory inefficiencies and mismanagement

Potential Solution: Reform of electric cooperatives, streamlining of approval processes for energy projects

Challenge: Lack of investment in power infrastructure

Potential Solution: Creation of incentives for private sector investment, increased government funding for rural electrification

Challenge: Vulnerability to natural disasters

Potential Solution: Hardening of power infrastructure, development of decentralized micro-grids for improved resilience

Challenge: Limited local technical expertise

Potential Solution: Investment in technical education and training programs focused on renewable energy technologies

IMPACT ON DAILY LIFE

Education: Students struggle with interrupted lessons and limited access to digital resources due to power outages.

Healthcare: Hospitals and clinics face challenges in providing care during blackouts, risking patient safety.

Business: Small enterprises struggle to operate consistently, while unreliable power deters larger industries from investing in the island.

Quality of Life: Residents cope with daily inconveniences and stress associated with unpredictable power supply.

Economic Development: High unemployment and limited job opportunities push many young residents to seek work elsewhere.

RENEWABLE ENERGY POTENTIAL

Solar: Mindoro’s tropical climate provides ample sunlight for photovoltaic power generation.

Wind: Coastal areas, particularly in northern Mindoro, show promise for wind farm development.

Hydroelectric: The island’s rivers and mountainous terrain offer opportunities for both large and small-scale hydro projects.

Geothermal: Some areas of Mindoro may have potential for geothermal energy development, though further exploration is needed.

GOVERNMENT RESPONSE AND FUTURE PLANS

Declaration of State of Calamity (2023) by Occidental Mindoro Capitol: Allowed for release of emergency funds to address immediate power crisis.

Senate Inquiry: Proposed investigation into recurring power problems and potential solutions.

Exploration of Nuclear Option: Department of Energy considering small modular nuclear reactors as a long-term solution.

Renewable Energy Push: Increased focus on facilitating renewable energy projects, including wind and solar farms.

Grid Modernization: Plans to upgrade and expand power distribution infrastructure across the island.

INTERNATIONAL COMPARISONS

Mindoro’s energy challenges mirror those faced by many island communities worldwide. Lessons can be drawn from successful initiatives in places like:

Hawaii, USA: Ambitious renewable energy targets and innovative grid management strategies.

El Hierro, Canary Islands: Achieved near 100% renewable energy through wind and pumped hydro storage.

Orkney Islands, Scotland: Became a net exporter of renewable energy through community-owned wind projects.

Sumba, Indonesia: Ongoing efforts to transition to 100% renewable energy through a mix of solar, wind, and biomass.

ECONOMIC IMPLICATIONS

Tourism Impact: Unreliable power supply hampers growth of Mindoro’s tourism sector, a potential economic driver.

Agricultural Productivity: Power outages affect irrigation systems and post-harvest processing capabilities.

Industrial Development: Lack of stable electricity deters manufacturing and other energy-intensive industries from establishing on the island.

Energy Costs: High reliance on subsidized diesel power strains both household and government budgets.

Job Creation: Potential for significant employment in renewable energy sector if large-scale projects materialize. (To be continued for the last part of this series)

Discover more from Mindoro Today

Subscribe to get the latest posts sent to your email.